No doubt many of you are dismayed at the outcome of the Atlanta TPPA talks, which saw a poor deal concluded, with only marginal market access for NZ dairy exports and confirmation of many of the worst fears of campaigns: investor-state dispute settlement provisions, costly copyright restrictions, increased costs for Pharmac, restrictions on the operation of SOEs and an array of other measures that amplify the influence of foreign investors and multinational corporations.

The NZ Government may be trumpeting its achievements, but the reality is far from rosy. As Bryan Gould notes in the NZ Herald:

The TPPA is a blueprint for extending the operation of those corporations without their having to bother with the restrictions that might be placed on them by national governments in the interests of their domestic populations.

It represents, in other words, a further, large, and largely irreversible step towards the absorption of a small economy like New Zealand into a much larger economy - an economy that is increasingly directed from overseas, not by politicians or even officials, but by self-interested and unaccountable business leaders.

Action continues!

On conclusion of the deal, It's Our Future called on the NZ Government to release the text and all other relevant decision-making material immediately. In the Auckland Council a resolution has just been passed calling on the government to release the final agreed text of the agreement and consult with the Council before further decisions are made.

Activists around the country are currently consulting on what next steps to take, and we will keep you informed of any actions that are coming up and how you can play your part.

International Treaties Bill

NZ First MP Fletcher Tabuteau (the man who brought you the Fighting Foreign Corporate Control Bill) now has a new Bill, the International Treaties Bill, which would shift the decision-making power to ratify to agreements like the TPPA from Cabinet to Parliament.

Professor Jane Kelsey's Latest Blog:

Sober reflections on the TPPA deal – and why we need to keep fighting

(We have reprinted Professor Jane Kelsey's latest blog on the TPPA from The Daily Blog below in full.)

After five and a half years Tim Groser and co finally did the deal. This was the worst possible day to be flying for 26 hours, trying to catch up with the details and unable to respond to media calls and the inevitable character assassination of those of us opposed to the TPPA.

There was no way the twelve governments were going to end the TPPA ministerial meeting in Atlanta without an agreement, especially after they got so close in Maui. They were out of time and too much political capital was at stake for any of the governments and ministers to have ‘failed’.

Instead, they failed us. New Zealand, along with Vietnam and Malaysia, are the biggest losers. We were always one of the most vulnerable players: no bargaining leverage, unrealistic demands pressed by an aggressive trade minister, and facing potentially more radical adjustments to satisfy US demands than participating countries that already have a USFTA.

We can take some solace in knowing that the battles fought nationally and internationally over the years, and the determination of staunch and courageous negotiators from some countries, stripped out some extreme proposals that became known through leaks. The final deal is still toxic, but it could have been even worse.

Without the text it’s impossible to precisely assess its implications, and we won’t get to see that for another month. Under the US Fast Track law, President Obama has to give 90 days notice to Congress before he can sign the TPPA, and must make the text public 30 days into that period. That gives the participating governments and their fellow travellers a month to spin the benefits, knowing that we don’t have the details.

Meanwhile, members of the US Congress and the corporate lobbyists who are ‘cleared advisers’ will get to see the deal. They will be all over it, seeking to change what they don’t like and making new demands. That will be the first of many opportunities for them to seek to rewrite the ‘final’ deal.

We do have some information. The USTR immediately released a 15 page summary of the 30 chapters. The Japanese government’s chapter by chapter account is more detailed and runs to 36 pages, but in Japanese; so, frustratingly for us, is the Ministry of Agriculture’s detailed explanation of Japan’s market access commitments. Canada has produced its own account . In New Zealand, MFAT has released a Q&A which says the only costs will be a 20 year extension to copyright law.

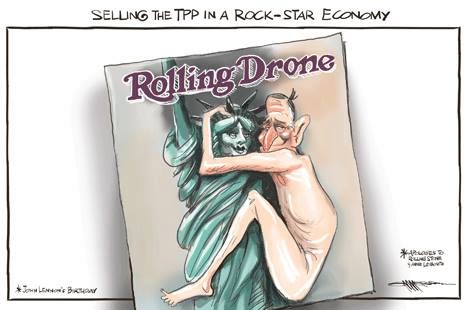

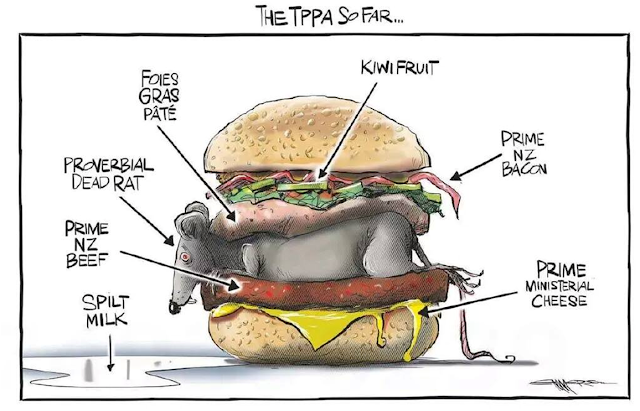

The spin has already begun. Fran O’Sullivan praised Groser’s ‘brinkmanship in the final brutal hours’ for securing New Zealand a deal on dairy that provided more than enough foie gras to compensate for any dead rats. What bollocks! It is true that Groser held out, arguing with USTR Froman until 5am. But he came out of it with bugger all.

In the assessment of US blog Politico:

‘Losers: New Zealand’s dairy industry, which is unhappy with the amount of access they’ve gotten. The Dairy Companies Association of New Zealand thanked Groser for making “every effort”, but said it was “disappointed that the agreement has not delivered a more significant opening of TPP dairy markets”. Surely, no-one really expected otherwise?

Claims the final package will be worth $2.7 billion a year for New Zealand by 2030 reflect another well-honed strategy. The MFAT figures expand concrete gains from tariff cuts by the time the agreement comes fully into force (at least another 15 years) through modelling and assumptions about intangible economic benefits. These figures rapidly gained traction, but cannot be authoritatively contested without the text and the studies or cost-benefit analyses that it relies on (the Minister has previously refused my Official Information Act requests for such analyses).

Minister Groser has continually sought to justify the government’s participation in the TPPA by insisting he would accept nothing less than a ‘high quality, commercially meaningful deal’ for dairy. For example, 20 June 2012 – Tim Groser’s Address to the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council: TPP and New Zealand’s export future:

‘TPP Leaders agreed in Honolulu in November … on a set of very high benchmarks, including elimination of all tariffs….This is going to challenge a number of the participants, especially on their most sensitive agriculture sectors, but if this is not to end as a farce, it is something they are going to have to do.’

Indeed, he promised to walk away from a deal if the TPPA failed to deliver those benefits. That was never going to happen, as Groser made clear at the end of the failed Maui ministerial. What we get instead at yesterday’s ministerial press briefing was yet more promises for the future and ‘trust us’ politics:

“Look, long after the details of this negotiation on things like tons of butter have been regarded as a footnote in history, the bigger picture of what we’ve achieved today will be what remains. It is inconceivable that the TPP bus will stop at Atlanta. The TPP bus will move on … Our industry structures will change in response to the opportunities of this agreement, and in future years, we can be absolutely certain that the depth of achievement we’ve been able to reach at this point in our collective history will be deepened and broadened and other people will join this agreement. Don’t ask me to be precise because I would then be forecasting the future, but I just want to tell you that while the difficult negotiations on things like dairy products, which in my country’s case ended at 5 o’clock this morning, we have always to deal with these realities in a trade negotiation, but the bigger picture is the reason we’re sitting here and that bigger picture will be profoundly important and beneficial to the generations of the people in our respective countries."

Echoes of the conveniently timed primer from Helen Clark: it would be unthinkable for New Zealand not to part of such a deal.

What do we know about the details? Let’s stay with dairy for now. The chess game said US concessions to NZ depended on new US exports to Canada and Japan. Canada granted new quotas phased in over 5 years: a 3.25% share of annual dairy production, with most directed to value-added processing (not what New Zealand produces). That is for all 11 members; we don’t know how much of that NZ got.

Japan will continue to regulate dairy imports through its state owned trading company. There will be a quota for imports of powdered skim milk and butter, raising from 60,000 tons to 70,000 in six years. Again, it’s not clear if NZ gets any of that. Tariffs will go from cheddar in 16 years.

Groser foreshadowed his sales pitch, now downplaying the significance of dairy, during the Atlanta press conference:

‘this establishes, in the long run, complete elimination of all tariffs on everything New Zealand exports with two exceptions. One is the beef tariff in Japan and the other are some dairy products, some of which will achieve tariff elimination and others have proven to be too difficult.’

There do appear to be more significant gains for beef, fruit, seafood, wine, forstry products, lamb – but, as the Australia Japan FTA showed, the devil will be in the detail. Most of these concessions will have (very) long phase out periods and ‘safeguards’ that allow claw-backs if they impact severely on the domestic industry. Some will have ‘special safeguards’ as well.

What are the downsides? Again, we need to see the details of the text, but the following is a start.

Affordable medicines was potentially affected by four elements: longer effective patent protections; new rules for drug companies’ monopolies over the data for new generation biologics medicines; and a ‘transparency’ annex gives Pharma more influence during Pharmac’s decisions.

The latest information I have confirms what Groser has said (contrary to Key’s earlier concessions that medicines will cost more). Australia’s hard won provision on biologics will protect New Zealand as well, subject to kickback in the US Congress and during the SU certification process. New Zealand’s patent laws currently meet the final TPPA threshold.

The transparency annex, although unenforceable, is still a provlem as it is likely to include oversight mechanisms and could inform the fourth remaining, serious element – the potential for investor-state disputes over the refusal patents (as in Canada’s Eli lilly case) or Pharmac’s decisions not to subsidise medicines.

The weak general exception that applies to public health apparently does not apply to the investment chapter. There is a tobacco exception but that only applies to ISDS, whereas Malaysia proposed a carveout from the entire agreement. The government could choose to block an investment arbitration over a tobacco control measure, but that appears to be a case by case election by a government that is already under pressure from Big Tobacco. But it seems they could still bring a case if they allege discrimination. States can still enforce the entire agreement, including the investment chapter. Tobacco policies are also still captured by the chapter on services (eg. advertising, retail) or labelling rules in the chapter on technical barriers to trade.

The investment chapter is based on the US model bilateral investment treaty, which is more pro-investor than New Zealand’s existing FTAs, including with China, Taiwan and South Korea. Investors are also expected to be able to use ISDS to enforce their contracts in the case of a dispute (eg Sky City or PPPs), even if that’s not provided for in their contract. The ‘most-favoured nation’ clause in those agreements means their investors now get these stronger protections. There are some procedural improvements to the old ISDS model but apparently still no appeals, no code of conduct, and no effective constraints on tribunals going rogue.

The governent continues to play down the risks from this, saying New Zealand has never been sued. Australia, Germany, and many other OECD countries had the same false sense of complacency until they faced massive damages claim for adoption health, environmental and anti-nuclear policies. The global backlash against ISDS, including by governments, cannot simply be ignored.

The cross-border services chapter has largely gone unremarked and needs to be viewed in tandem with current 24-party negotiations for a Trade in Services Agreement (TISA). The chapter will require governments to maintain the current failed risk-tolerant light handed approach to regulation of services. Current levels of liberalisation will be locked in for many services, with a ratchet that automatically locks in any new liberalisation. Similar annexes will apply to the investment chapter. We don’t have the annexes to see which services and investments they apply to, but the Prime Minister has already conceded it would be impossible to strengthen restrictions on foreign investors in the residential property market.

Future governments may not be able to establish new state-owned enterprises (eg insurance, broadcasting, research) that require state support which foreign competitors say has an adverse effect on their activities. Again, we need to see the details on this and other impacts of the chapter.

Future governments may not be able to establish new state-owned enterprises (eg insurance, broadcasting, research) that require state support which foreign competitors say has an adverse effect on their activities. Again, we need to see the details on this and other impacts of the chapter.Twenty years longer for copyright will impact on libraries and researchers, depending on the exceptions. New provisions are expected to allow ISPs to block websites if infringements are alleged (not proved) and new criminal penalties would apply for circumventing digital locks. The global tech companies claim to have succeded in stopping ‘localisation’ rules, where countries require data to be stored within the territory (localisation).

There are numerous provisions and a whole chapter dedicated to ensuring that commercial interests have rights to influence government decisions on policy and regulation.

This is just a start. New Zealanders therefore need to ask a simple question: who gave the Prime Minister and Trade Minister the right to sacrifice our rights to regulate foreign investment, to decide our own copyright laws, to set up new SOEs, and whatever else they have agreed to in this secret deal and present it to us as a fait accompli?

The campaign against the TPPA now moves into a new phase in each country: educating people about what the text means for nations, communities and sectors, countering the spin that is already at full tilt, and then stopping governments from adopting it.

That is crucial not just to save individual countries from the toxic deal. If enough governments hold back they cannot get the critical mass needed to bring the TPPA into force. This happened with the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) – thanks to opposition within Europe it has still not been ratified by the minimum number of countries required. It is not clear how many and what size signatories will be required for the TPPA.

Clearly the US remains pivotal. Opposition is already welling up inside the Congress from both parties on a wide range of issues. Memories of Obama’s failure to secure Fast Track first time around in a bruising political contest that alienated his own supporters potend ill in an election year.

In my next blog I will explain in detail the political processes that will be used here, and in the US, and what opportunities they present to derail the TPPA.

No comments:

Post a Comment